24 Hours as the On-call Doctor in the Torres Strait

Note: The purpose of this site if to provide free open access medical education (FOAMed) in the context of rural and remote health. Though all stories have been inspired by real cases, all identifying details such as names, ages, locations and background descriptions have been thoroughly changed to ensure the absolute privacy of the patients, families and communities we serve.

Note: The purpose of this site if to provide free open access medical education (FOAMed) in the context of rural and remote health. Though all stories have been inspired by real cases, all identifying details such as names, ages, locations and background descriptions have been thoroughly changed to ensure the absolute privacy of the patients, families and communities we serve.

24 Hours as the Doctor On-call in the Torres Strait

Manning the on-call phone for the Torres Strait is one of my favourite jobs. There is a doctor rostered to this job at all times and entails being the first point of call for any medical query in the region.

The Background

The Torres Strait is a spectacular group of remote islands located at the very tip of Queensland between Cape York and Papua New Guinea. The most northern islands are only 4km offshore from the PNG mainland. The region spans 48,000 square kilometres, which is an area bigger that Switzerland or Holland, and is comprised of 274 islands though only 17 are inhabited. The Northern Peninsula Area (NPA) comprises five communities on the northern tip of Cape York Peninsula. The population of approximately 14,000 are spread over the Torres Strait islands and communities in the NPA.

Populations of these communities vary from as little as approximately 60 people on Stephen (Ugar) Island to 2900 people on Thursday (Waiben) Island. People who identify as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander (ATSI) persons account for 90.7% of the population of the region.

The 16 primary health centres in the Torres Strait Islands are staffed by nurses and indigenous health workers with a doctor visiting every few weeks so between visits any cases which need a doctor’s input will be run through the on-call phone. Sometime the calls will need to be taken from NPA communities depending on local rostering. Calls can range from providing advice on treatment of impetigo to coordinating a cardiac arrest via videolink. Each day I find new surprises; it is never dull and almost always very busy.

There is something very challenging about assessing a patient via a telephone. In face-to-face medicine so much of my initial thoughts are based on how sick or well a patient looks and without the ‘eye-ball assessment’ evaluating and responding to a situation accurately over the phone can be challenging. I utilise video-link frequently to help overcome this and have learnt to adapt my practice to make sure I ask the right questions to provide a safe assessment.

The Situation:

Though most shifts are extremely interesting and enjoyable, I had one particular 24 hour stretch on-call which stands out and is a perfect example of what remote medicine involves. The essence of working as a rural generalist is adaptability, resilience and the willingness to ‘wear-many-hats’ – there are no specialists for more than 1000km and patients can become sick very quickly, so it is necessary to be able to step-up to provide critical care when necessary and manage primary care, emergency, paediatric, obstetric and psychiatric presentations. It is often challenging, sometimes stressful, but always a fulfilling job.

Diabetic Ketoacidosis

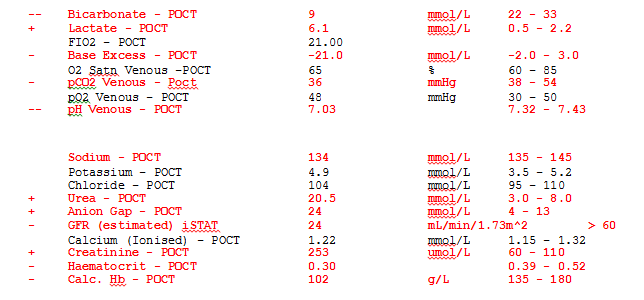

After a full day in the GP clinic in the dry season, I took handover for the on call at 5:30pm. The first patient of the day was already in the emergency department having been transferred by the rescue helicopter from one of the northern islands near the PNG border. The patient was a 15-year-old girl who had been carried from her village in PNG and transported in a dinghy across the water as she was vomiting profusely and feeling weak. The local hospital in PNG had not been able to supply her insulin and she had run out. Initial point-of-care blood tests showed severe metabolic acidosis, renal failure and raised ketones:

She was retrieved to Thursday Island Hospital by a GP anaesthetist and paramedic and treated with fluids, insulin, potassium, broad spectrum IV antibiotics and while in ED she required noradrenaline via a central line to keep her MAP above 70. Transfer to Cairns Hospital ICU through the Royal Flying Doctor Service (RFDS) was arranged. The journey of over 1000km would involve a fixed wing plane travelling from Cairns to Horn Island, where the retrieval team would transfer to a helicopter to reach Thursday Island and collect the patient.

A Fall

Just as I was about to grab some dinner the ambulance sirens alerted me that a new patient was on his way. A 20-year-old male was brought in following an accident. He and his friends had been celebrating a win at the football carnival and had been jokingly jostling each other on a first-floor balcony. A playful tackle had gone wrong and the patient had slipped from the balcony landing with his head taking the force of the fall. This was witnessed by friend who reported that became immediately limp and unresponsive after the impact. No seizures were noticed. He was placed in the recovery position and was spontaneously breathing.

When he arrived in ED ABC’s were intact and his initial GCS was 11. He had vomited twice. Apart from a moderate parietal haematoma there were no signs of skull fracture and no localising signs on a brief neurological examination. The were no bony steps, no haemotympanum or CSF rhinorrhoea. Secondary survey did not demonstrate any obvious long bones fractures, or chest or pelvic trauma. A bedside FAST scan was negative, and his abdomen was soft. C-spine films showed soft tissue swelling anterior to the upper c-spine, but no definite fractures. The remainder of the trauma series x-rays were unremarkable. A plan with the Cairns ED specialist was made to transfer for a CT c-spine as I was quite worried about the potential for a fracture.

As the patient began to wake up and learn the plan to transfer to Cairns he became unsettled. He said he was fine and wanted to go home to watch Netflix despite complaining of a neck pain. Regardless of a thorough discussion around the reasons for further investigation and the risk of not treating a broken neck, he was adamant he was leaving. There is no formal security presence in the hospital, so his family who were gathered in the waiting room were essential in persuading him to stay and in organising a big group of his uncles and cousins to sit by his bed for support.

Unfortunately, there was no potential to add this patient to the RFDS flight transporting the first patient of the night, so it would be early morning before another retrieval team could be sent from Cairns. A retrieval request was tasked. A tertiary survey showed several superficial lacerations over his limbs and chest and bony tenderness over the upper c-spine, but no other obvious injuries. Observations were normal, GCS remained 15 and with the support of his family, the patient stayed calm and settled. He was treated with an ADT, ondansetron and maintenance fluids and had no further episodes of vomiting. Spinal precautions were put in place and he received one on one nursing care with regular neuro observations.

STEMI

By this time, it was 11pm and dinner was in sight, when I received a phone call from a relieving nurse on one of the eastern Torres Strait islands over 200km away. An octogenarian visitor to the island had presented to the clinic with 12 hours of central heavy chest pain radiating to both arms associated with a drenching sweat and nausea. Point-of-care troponin was 5.2 and an ECG was faxed through which showed ST elevation in the anterior chest leads.

After initiating aspirin and morphine, I immediately called the cardiologist in Cairns for advice regarding lysis in the setting of 12+ hours of pain and regular apixaban for previous PE. I texted him the ECG. Transfer to the nearest cardiac cath lab would involve a helicopter flight of over 200km one-way and then a 1000km flight to specialist care. The decision was made to provide thrombolysis.

On the island there were two relieving nurses and one health worker, but no doctor. Neither nurse had been involved in previous thrombolysis and only one vial of metalyse was on the island. It was important not to waste that vial or treatment would be delayed at least another 3 hours until the helicopter with a GP anaesthetist landed on the island. Careful explanation was given regarding the process, how to prepare the drug and what emergency drugs would be needed in the setting of arrhythmia or arrest. In the meantime, I requested retrieval. Lysis resulted in good resolution of symptoms, however the ECG changes persisted. The patient arrived on Thursday Island about 5am, pain resumed and a GTN infusion was started in consultation with cardiology while awaiting transfer to Cairns for interventional cardiology.

Acute Rheumatic Fever

The phone was fairly quiet for a few hours and my coffee was starting to kick in when I received a call about a 5-year-old male from one of the near western islands who had a fever to 39.2 degrees Celsius with no clear source. Upon questioning, he had recovered from tonsillitis two weeks ago, over the last few days had been limping with a sore knee and ankle and he complained of inspiratory chest pain. Examination and urinalysis didn’t demonstrate a source. Chest CXR was normal and his ECG showed a PR interval 0.16 seconds (upper limit of normal for age).

I was suspicious the he may have acute rheumatic fever (ARF). I treated him with IM Bicillin, paracetamol and ibuprofen and arranged transfer on a commercial flight for an echocardiogram as our visiting paediatric cardiologist would be on Thursday Island the next day. His ESR and CRP were raised, and he fulfilled criteria for a diagnosis of ARF with carditis, fever, polyarthralgia and raised inflammatory markers. A regime of Bicillin injections every four weeks will continue until he is at least 21 and he will need regular dental checks and echocardiograms. His family were provided education regarding ARF and he was referred to the Rheumatic Heart Disease Register.

Crocodile Bite

The rest of the day was busy with fairly standard phone queries from the outer island clinics. Our STEMI patient had been treated in the cath lab, the patient with DKA was improving in Cairns ICU and the patient who had fallen had a confirmed unstable C2 fracture on CT. Things were starting to wind down about 4pm when I received a phone call about a patient who had been bitten by a crocodile.

The patient, a 35-year-old male, had been spearing fish in the mangroves on an uninhabited island with several friends. He reports swimming along when he felt something brush the back of the leg and as he turned around to see his foot grazed the inside of a crocodile’s mouth. He subsequently kicked the crocodile in the head and it swam away. This was witnessed by three of his friends from the dingy who confirm his story and report the crocodile was about the size of a single bed! He then drove the boat back to his island and attended the local health centre.

Talking to the local health worker about the situation he tells me that it was nesting season and the crocodile was likely just giving a ‘warning-bite’ to get the diver to move on. The patient was very lucky to survive with a small chunk of missing skin over the dorsum of a foot. Clinical photos were sent through and I treated him with an ADT, prophylactic antibiotics and good wound care.

I reflected on the previous 24 hours as I walked home with a colleague and remarked on the extraordinary variety of clinical cases which presented over the day. It was a fantastic reminder to me of the unpredictability of rural generalism and the immense fulfilment and challenge associated with working in remote Australia. Despite the geographical remoteness, logistical challenges, scarce resources and lack of subspecialist services, I think our team does a truly remarkable job in providing care for this community. I am proud to be a part of a team of resilient, motivated and dedicated doctors.

That’s what I call a complete day!

I also worked for many years in remote areas, as the only available doctor .

It’s a strange feeling ,once you realize that you are really helping people, but on the other hand , sometimes you wish you could have better conditions, more knowledge and better skills, as well as you may have doubts if you could have done something different for your patient’s management.

Most doctors working in big cities have no idea what we are talking about…

My congrats to you. You should be proud of being practicing the “real medicine”.