Māori Health Matters

Confessions of a racist Doctor.

I am racist.

I was born in an Australian capital city, a nation with a history of political non-compliance with The Universal Declaration of Human Rights to its mistreatment of indigenous peoples since 1788.

The 1901 White Australia policy excluded people of non-European ethnic origin, especially Asians (primarily Chinese) and Pacific Islanders from immigrating to Australia.

As a private school student, University was a foregone conclusion. I was the sole medical student selected for a military scholarship in 2003; I studied without financial burden. I graduated, secured employment as an Army Doctor until 2011 when I began a career in Rural Medicine.

Self-righteousness, born of white privilege propelled me into remote Australia with the certainty that I had something unique to offer indigenous communities. With newly gained medical skills, I brought all the historical and institutionalised racism of the organisations that shaped me. It is only now after nearly ten years of working with indigenous people that my eyes are opening.

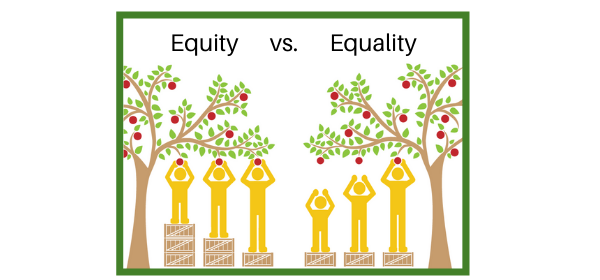

I live now in New Zealand, where according to Carla A. Houkamau’s 2016 article general practitioners are less likely to prescribe prophylactic therapy to Māori and Polynesian children. Pākehā doctors spend 17% less time interviewing Māori than patients from other ethnic groups. Māori patients are less likely than other ethnic groups to receive chemotherapy and, if they do, are more likely to experience a delay of at least eight weeks before starting. Māori men are less likely to receive medical intervention for cardiac disease or to receive screening for, and treatment of, ischaemic heart disease than Pākehā.

I am racist. Not in the outdated definition of intentional harm directed against someone of another race. But in an entirely more subtle and pervasive way. Internalised and implicit biases of my socialisation blinded me to the systemic discrimination embedded in organisations of which I am a part. I have caused harm and I am sorry.

Of some wrongs, I might never know. Who will tell me? Not the victims, they risk too much, nor the privileged, they are blind or invested in maintaining the status quo. Racism is an uncomfortable issue; egos are not strong enough to bear the criticism. Instead, we defend our position, feelings of guilt, insult and hurt.

I am racist, and I challenge my colleagues to examine their prejudices. You are racist. It is not your fault. But it is your responsibility to examine and label the unconscious bigotry that guide our practice and sustain health inequality.

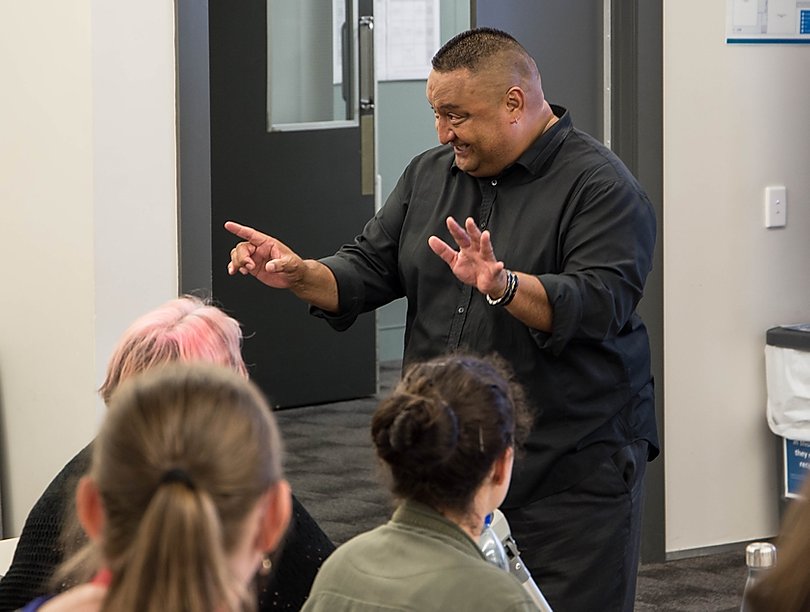

Be open to criticism. Build discussion around internalised bias, include it in the teaching of junior healthcare workers, and our professional development. Speak of it at journal clubs, peer review and grand rounds.

Thanks to Lakes DHB for introducing me to Hone Hurihanganui and his challenge to the implicit bias of healthcare workers. I applaud my organisations efforts toward equity in health care.

If your organisation does not insist on cultural competence training, ask why.

Thank you for having the courage to admit mistakes (especially in the important area of Medicine) and take responsibility for one’s actions and so doing move on to a better place.

What a wonderful world it would be if each of us did this every day even in very small ways.