Researching Remotely

You just can’t miss it. A grass green building with multi-coloured panels representing our frangipanis, sea and sand. The Australian Institute of Tropical Health and Medicines (AITHM) Tropical Research Centre (or as locals like to call it – the colour-colour building) was officially opened last fortnight on Thursday Island.

James Cook University (JCU) and AITHM academics have enthusiastically touted this building not only as a research facility and study base for JCU students, but also as a place the community can hold meetings and events. As I toured building I was shown the flash meeting rooms, accommodation facilities and the one shiny physical containment level 2 lab filled with brand new equipment not yet out of its packaging. My eyes glistened as I inspected the fume hoods, centrifuges and PCR machines! When someone describes themselves as a researcher, I envisage lab coats, pipettes and white mice. And is it any wonder – when laboratory research the only research experience I have had in my career to date. But research is so much more than that. Especially in remote communities such as the Torres Straits.

Past research involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people has been criticised as inherently biased and disempowering. In the Torres Straits I have heard many stories from locals who have unfortunately had negative research experiences. They describe research groups (predominantly comprised of non-Indigenous people) who swoop in, collect their data of interest and swoop out. Locals are uncertain about the study outcomes or indeed how the project is improving their community’s health. During a research governance community consultation here on Thursday Island last year one local Elder declared:

“We have been researched to death,

it’s time we research ourselves back to life!”

So in a remote setting, how do you undertake culturally appropriate, outcomes-based research to benefit the communities best interest? To be honest, I am still navigating the answer to this question myself, but the process of undertaking research on Thursday Island this year has been a most humbling experience. Here are some things I have learnt along the way:

1. It’s not about the shiny labs, papers published or grants. Effective and ethical research has to be owned and conducted by Indigenous communities, choosing their own research priorities. As a non-Indigenous person undertaking clinical research in a predominantly Torres Strait Islander community, at times I feel conflicted, am I just another researcher sweeping in, creating more collateral damage? I have come to the realisation that what is more important than the research, is the local research capacity building; and I’m thrilled that we have secured funding for our health services to employ an Indigenous Research Officer for 2019.

2. Consultation, collaboration and communication with the community is key. Here on TI, we have a JCU Torres Strait Health Sciences Consultative Research Committee, chaired by a local Torres Strait Islander Elder. Their aim is to not only set the research priorities in the Torres Straits, but also vet proposed projects. Undertaking research in other remote communities may involve consultation with Elders, community members or the local council.

3. It’s all about tangible research outcomes and knowledge translation. At the end of the day, research in Indigenous communities is owned by that community. They deserve to know how the results will bring their community back to life. Menzies Hot North initiative is doing just that and aims to promote effective transfer of research outcomes into health policy and practice. The research projects I’m involved won’t be complete until their findings shared with the community.

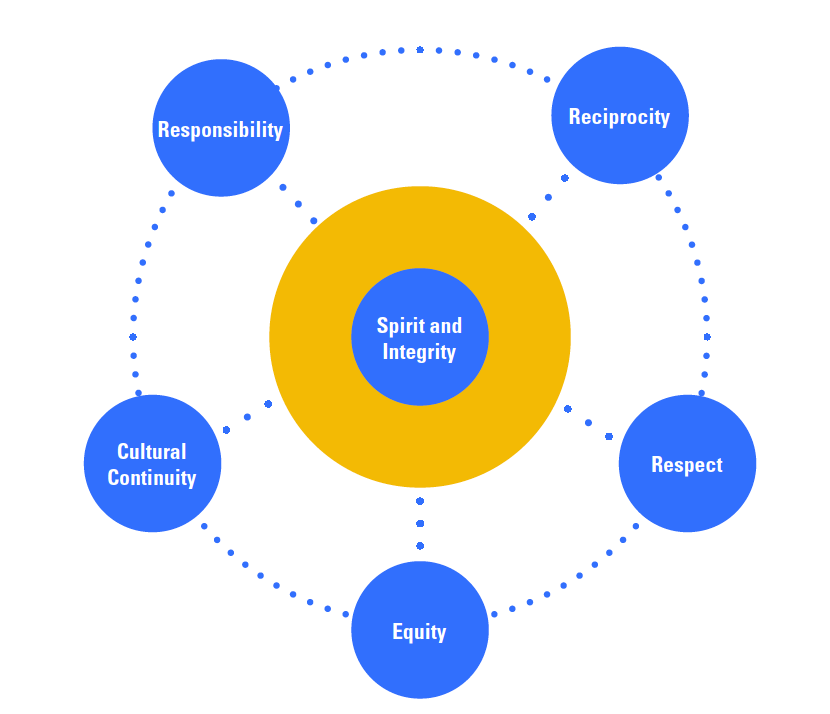

4. The NHMRC ethical conduct in research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and communities guidelines for researchers and stakeholders document is your best friend. Check it out here. Researchers undertaking research in Indigenous communities are required to submit a Human Research Ethics Application to their local ethics committee and describe how the research will address six core values: responsibility, reciprocity, respect equity, cultural continuity and spirit and integrity. As a clinician, I would highly recommend reading this document – even if you never intend on participating in research. It explains vital principles that make up the fabric of Indigenous culture.

5. It takes time. Lots of time.

So as the colour-colour building opening celebrations have faded with the setting sun, a new chapter begins. I hope 2019 will breathe life into a sustainable, community-owned culture of research. And with the timely Australian Medical Research and Innovation Priorities 2018 – 2020 released last week including Primary Care and Indigenous health, it is an exciting time for research in the Torres Straits.

Nice