Iron Deficiency Anaemia

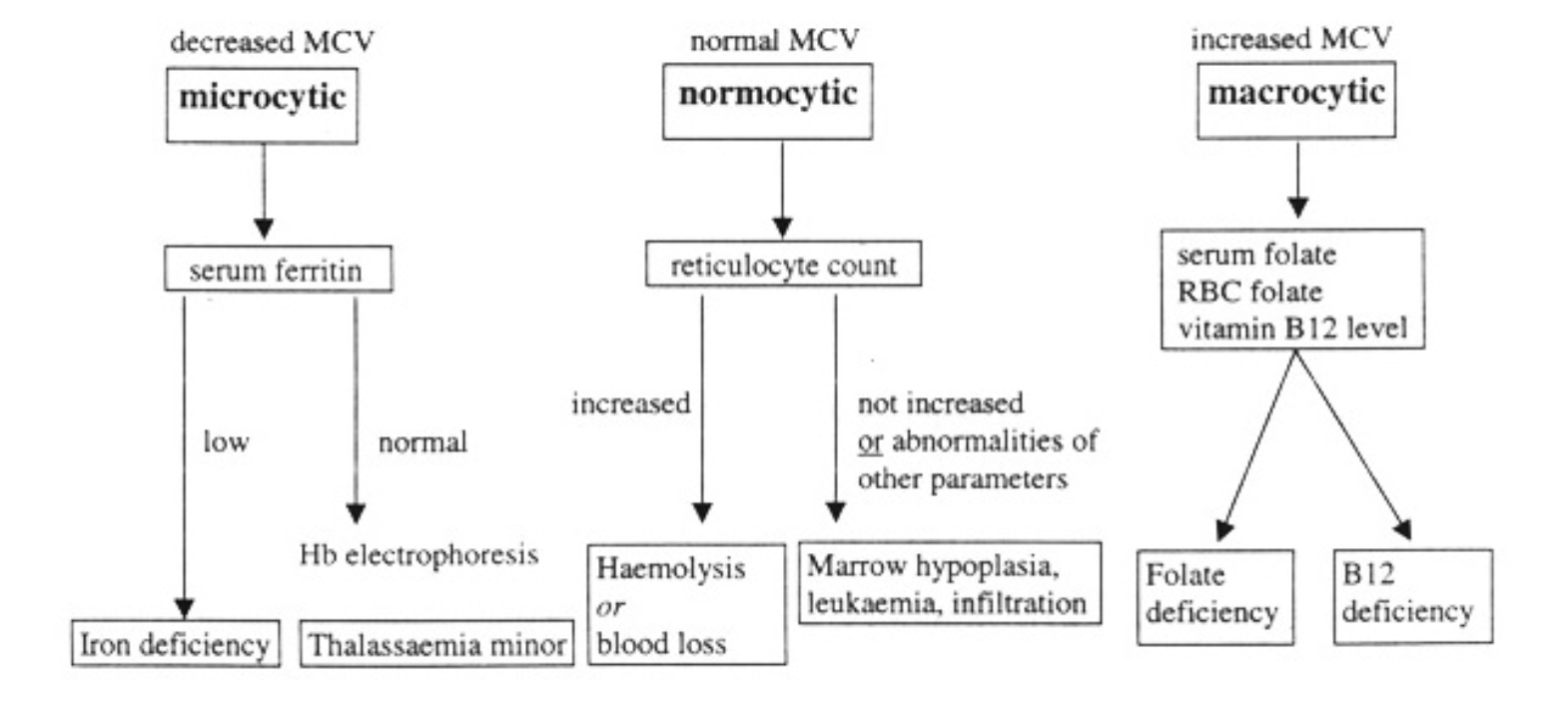

As we improve our preventative health screening practices in Remote Indigenous Health we inevitably encounter incidental abnormalities in routine pathology. Given our limited resources and developing recall systems, what do we do about them?

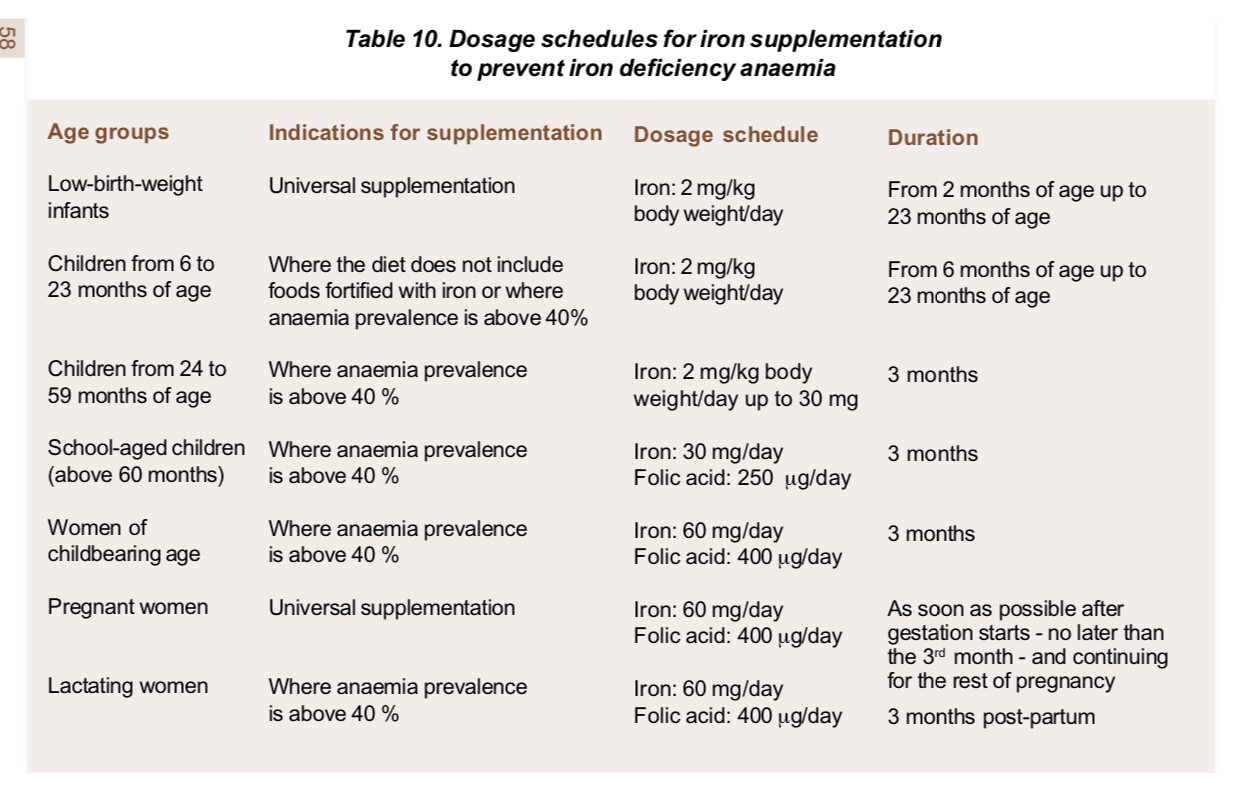

The World Health Organisation report the greatest prevalence of iron deficiency in children occurs during the second year of life, due to low iron content in the diet and rapid growth during the first year. In areas with a high prevalence of hookworm infestation, school-aged children as well as adults can also develop significant iron deficiency.

Some Australian guidelines recommend screening all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children however current WHO guidelines have recommend children are screened at age 6–9 months and repeat at 18 months with all cases of iron deficiency anaemia recalled for follow up testing. Australia’s national guide for ATSI has followed this lead. Iron rich foods such as meat and fortified cereals, leafy green vegetables and vitamin C should be routinely encouraged.

As the population prevalence it the Torres Strait is currently unknown we will continue with national guidelines born out of WHO screening recommendations. Our priority groups for screening, treatment and prevention are preschool children and women of child bearing age. Menstrual blood loss is the most common source in menstruating women. Iron deficiency anemia in adult men and nonmenstruating women warrants further gastrointestinal investigation for occult blood loss, including evaluation for gastrointestinal malignancy.

Oral iron replacement is the most appropriate first-line treatment in the majority of patients. Its efficacy can be limited by poor patient compliance due to the high rate of gastrointestinal adverse effects and the prolonged treatment course needed to replenish body iron stores.

Intravenous iron preparations are indicated when oral iron therapy has failed or rapid replenishment is required. Ferric carboxymaltose can rapidly deliver a large dose of iron, making it the preparation of choice for outpatients. Despite their excellent safety profiles, all intravenous iron preparations carry the risk of anaphylaxis. Patients require monitoring and access to resuscitation facilities.

We would love to hear from colleagues working in indigenous health, who if anyone do you screen?